Many people know Dr. Terry Simpson as a TikTok-famous surgeon with over 1 million followers eager for his health-related hot takes.

Turns out that is the least interesting thing about him.

An Alaska Native of Athabascan descent, Dr. Simpson was born and raised in postcard-worthy Ketchikan, Alaska. He started his career in molecular research and virology before going to med school, and when he became a fellow of the American College of Surgeons, he did so as the very first Alaska Native.

Dr. Simpson started sharing his medical expertise with the public long before TikTok existed — or any social media, for that matter. Writing was simply a means of sharing information with his patients, and he wrote several books and even became the resident physician for Daytime TV. (He eventually married the producer!)

More recently, Dr. Simpson fought through the COVID-19 pandemic at a hospital in California, where he, by his own admission, worked harder than he ever had in his life “doing things [he] never thought he would do.”

Many medical staff were burned out by the experience, Dr. Simpson says, because nobody believed the horror they were going through. "That's disinformation for you. You fight it not for the true believers of the nonsense; you fight it for the people who might be influenced or misguided."

Now semi-retired, Dr. Simpson spends his days fighting the medical "fake news" on the internet, doing podcasts, and writing 1,000 words each and every day.

We sat down to chat about the effects of writing on health, and spoiler alert: this interviewer cried twice.

ANNIE COSBY: Is there any research on how writing affects our cognitive health?

DR. TERRY SIMPSON: Scientifically, we know that the more active and engaged you are mentally, the better you will do long-term. Now, we don't know if that's a correlation or causation.

But we do know that the brain has what we call a plasticity to it.

Pretend you have a non-devastating stroke and lose some ability in your fingers. We know that, over time, your brain can assign the use of those fingers to other parts of the brain that aren't damaged, and you may relearn to use them.

There are some diseases in the brain that we don't yet have a way to fix. But we know, for example, that if you eat a Mediterranean-style diet, you have a 53% lower chance of developing Alzheimer's disease. And we also know that if you keep your brain active, even if you do have an inevitable disease of the brain that we can't yet cure, you are better for much longer.

People who keep mentally active — people who write, people who are involved in music, people who speak different languages … They keep the brain active.

Think of the brain like a muscle. The worst thing you can do is become passive.

Becoming passive is, you know, watching television, scrolling through social media. Stuff like that.

By writing, you are incorporating different parts of your brain, like your memory, and you're doing physical things, even if it's just typing with your fingers. You’re also listening. You're doing a lot of things that are helping your brain stay active.

People who keep mentally active — people who write, people who are involved in music, people who speak different languages … They keep the brain active.

AC: That's fantastic. Before we dig into that, let's back up a bit. You first started writing to share medical expertise decades ago. How has writing changed over that time?

TS: Well, when I first started writing, it was pretty easy. There wasn't anything to distract you other than a telephone sitting on your desk. Very few people would email you — there wasn't constant spam coming through.

And I love typing, so I could sit at my computer and type away.

After that, there was a long period where I didn't write anything. There were too many distractions, like the internet. On top of that, I discovered that I love editing. So I would edit the same thing for maybe a month and not write anything new.

I can edit all day long and not put a damn thing down.

I can edit all day long and not put a damn thing down.

AC: I can relate.

TS: It was frustrating! I have all this stuff in me that I need to get out.

Before, I never felt like I had the time for writing, because I would sit down at my computer, start writing, and then I would look something up and I would just fall down rabbit holes. Or an email would pop up, and then I would get stuck on social media.

Next thing you know, I hadn't written a thing. And it was always in the back of my mind: I'm not writing, I'm not writing, I'm not writing.

Then, you guys announced a challenge this past June. And I said, why don't I try doing a thousand words a day? Maybe I'll even win something. And that started gamifying it for me — I was trying to get that prize.

And I didn't win the prize, but you know what? I've been writing every day, which is an amazing prize. I can't thank you guys enough.

And it was always in the back of my mind — I'm not writing, I'm not writing, I'm not writing.

AC: And you’re still going?

TS: Today is day 47 of writing 1,000 words a day.

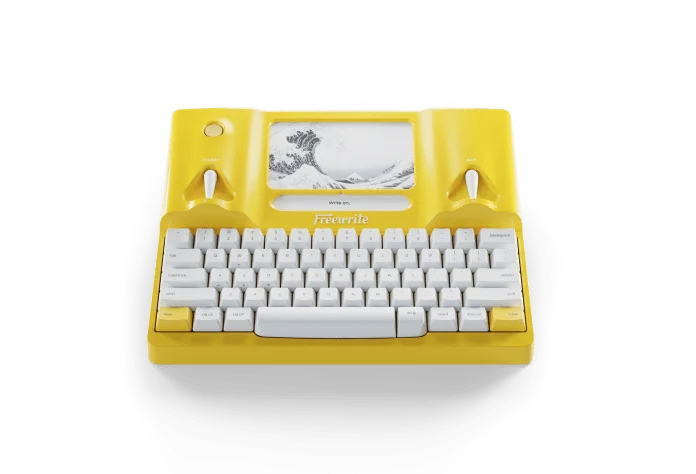

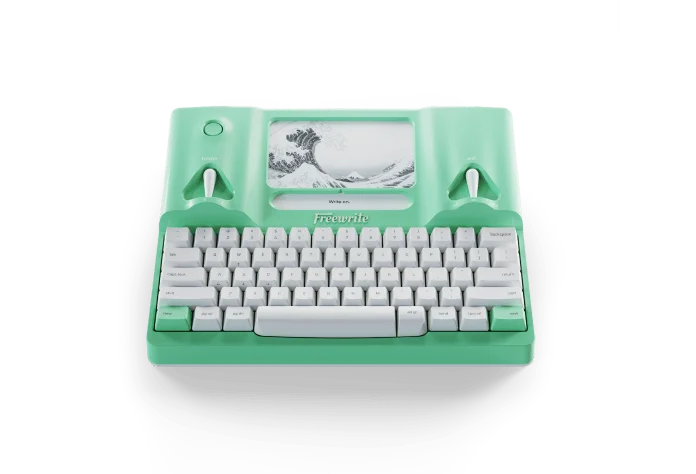

Usually at about 4:30 p.m. Pacific, I do a live on TikTok, and either just before or after that, I pull out my Traveler and say, What am I going to write about today?

AC: You reference a lot of scientific studies in your work. How do you handle that while freewriting?

TS: If I know there was a study about something somewhere, I might look for the study and put what we call the PMI — the public med identifier number — in there so I can use it later to research and grab a reference. It helps me stay on task.

And what I've discovered is that it changed the way that I write. It's coming out more in my own voice.

Sometimes when you write, you write not in your voice but in the way you think you should sound, right? But I'm not a Hemingway, I'm … whoever I am.

Sometimes when you write, you write not in your voice but in the way you think you should sound, right? But I'm not a Hemingway, I'm … whoever I am.

AC: *laughing* And what does your voice sound like?

TS: It’s a little humorous. Not so serious. I can’t help the humor. I'm a dad — as soon as my son was born, I started with the puns.

AC: I bet you were punny before that.

TS: Well, surgeons have a dark humor, so there's sometimes a little of that, too. And writing in that voice is good for me. But you can’t find that voice if you don't write, you know?

AC: And you have to be open to just seeing what comes out. If you can let go like that, it’s so much fun.

TS: Oh, writing every day has been absolutely joyful. It’s like suddenly rediscovering something you love.

It's like, “Oh my gosh, there's ice cream. I forgot about ice cream! I really like ice cream. Let me have ice cream every day.”

Except it's probably healthier than having ice cream every day.

[Writing again] is like suddenly rediscovering something you love. It's like, “Oh my gosh, there's ice cream. I forgot about ice cream!"... Except it's probably healthier than having ice cream every day.

AC: Yeah, the impact of reading and writing on the health of the brain is pretty cool. Have you seen that firsthand at all in your work?

TS: Absolutely. I now do a lot of work in nursing homes, and I've had the privilege of taking care of a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist and other, just, very interesting people. I had a patient who had been a college professor of literature but had mentally declined from a bad case of vascular dementia.

This guy had a Ph.D. in literature from Harvard. And when I started taking care of him, I'd say, "Who's your favorite author?" *snaps* “Henry James.” He’d answer immediately.

Now, I had never read Henry James, who, by the way, writes differently than most authors, quite unique and distinct — and sometimes difficult to get through. But I started reading Henry James.

And whenever we would talk about Henry James, this patient's eyes would light up. I’d say, "What should I read next?" *snaps* “Daisy Miller.”

This guy, if you were to look at an MRI of his brain, has lost a lot of volume from this disease, and he still gets excited about reading and books and stories.

This guy, if you were to look at an MRI of his brain, has lost a lot of volume from this disease, and he still gets excited about reading and books and stories.

AC: *tearing up* It’s still all there inside him!

TS: He may not have everything that he had before, but some of it's still there. To have filled up his mind with some of the great literature of the world that still causes him to smile?

I think the stuff I see on TikTok is not going to be there, if I ever mentally decline. I would rather have it filled with the good stuff.

I think the stuff I see on TikTok is not going to be there, if I ever mentally decline. I would rather have it filled with the good stuff.

AC: You helped your dad write a book, too, right?

TS: Yes. My father was half Athabascan and half Welsh. When his parents divorced, because his mother was Native American, she did not get the boy. There was not even a question about that. Native Americans at that time were not citizens of the United States.

But my grandfather was some kind of hunter or trapper and couldn't raise my father, so he took my father, at four years old, to the Jesse Lee Home, an orphanage. There were a lot of orphanages in Alaska because there was a lot of tuberculosis and measles, which decimated the native population and created many orphans.

My dad wanted to write about his experience there, so he gathered all these pictures and things, and I helped him write it. We self-published it on Amazon.

One of his greatest joys toward the end of his life was this book. When my mom got sick with vascular dementia, she and my dad both went into assisted living. People would talk to my dad and find out about his book, and they would read it and learn about his story, and he loved that.

AC: *tearing up again* It’s the power of sharing your story with other humans.

TS: Absolutely. After my mom died, my dad decided to move back into his house, and he lived there until just a couple days before he died.

He was getting ready to write another book, and he just sort of ran out of time. Still sharp as a tack up until the last breath.

AC: Because he was writing!

TS: *laughs* Maybe.

AC: *composing herself* Before we end, can you share with everyone what you’re working on now?

TS: Sure. I'm writing about dietary algorithms.

AC: Dietary what?

TS: Basically, weight loss is not going to be a problem in about five years. We're on the precipice of some ground-breaking medications that are going to be cheap and readily available, by pill ... but we still gotta eat.

These weird little fad “diets” are going to be gone, and we're going to have to go back to what we should have always been focused on, which is the algorithm for eating for one's health. We need to relearn how to eat.

AC: I never thought about how the availability of things like Ozempic might affect wider society’s relationship with food…

TS: It’s coming. Weight is tangible, but you can’t see your arteries, right? The mindset has to shift to “I don't want die of a heart attack. I want to decrease my risk of heart disease and cancer, etc.”

The whole point of what I'm writing now is, How can we help you make your future better?

AC: What’s your #1 piece of advice for people out there who want to write but aren’t writing?

TS: You have to realize your writing is not going to be perfect, but it doesn't have to be perfect… You just have to let the words out.

And the next thing you know, you're writing again, and it becomes a part of your routine. And then it becomes the joyful part of your routine.

There are a lot of great writers out there. They just don't know it yet.

There are a lot of great writers out there. They just don't know it yet.

Follow Dr. Simpson on: TikTok | Instagram | X | Facebook | YouTube

Learn more about the doc at terrysimpson.com.

Note: No material in this email is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your doctor or qualified health care provider.